Democrats are dead in the land of Dixie.

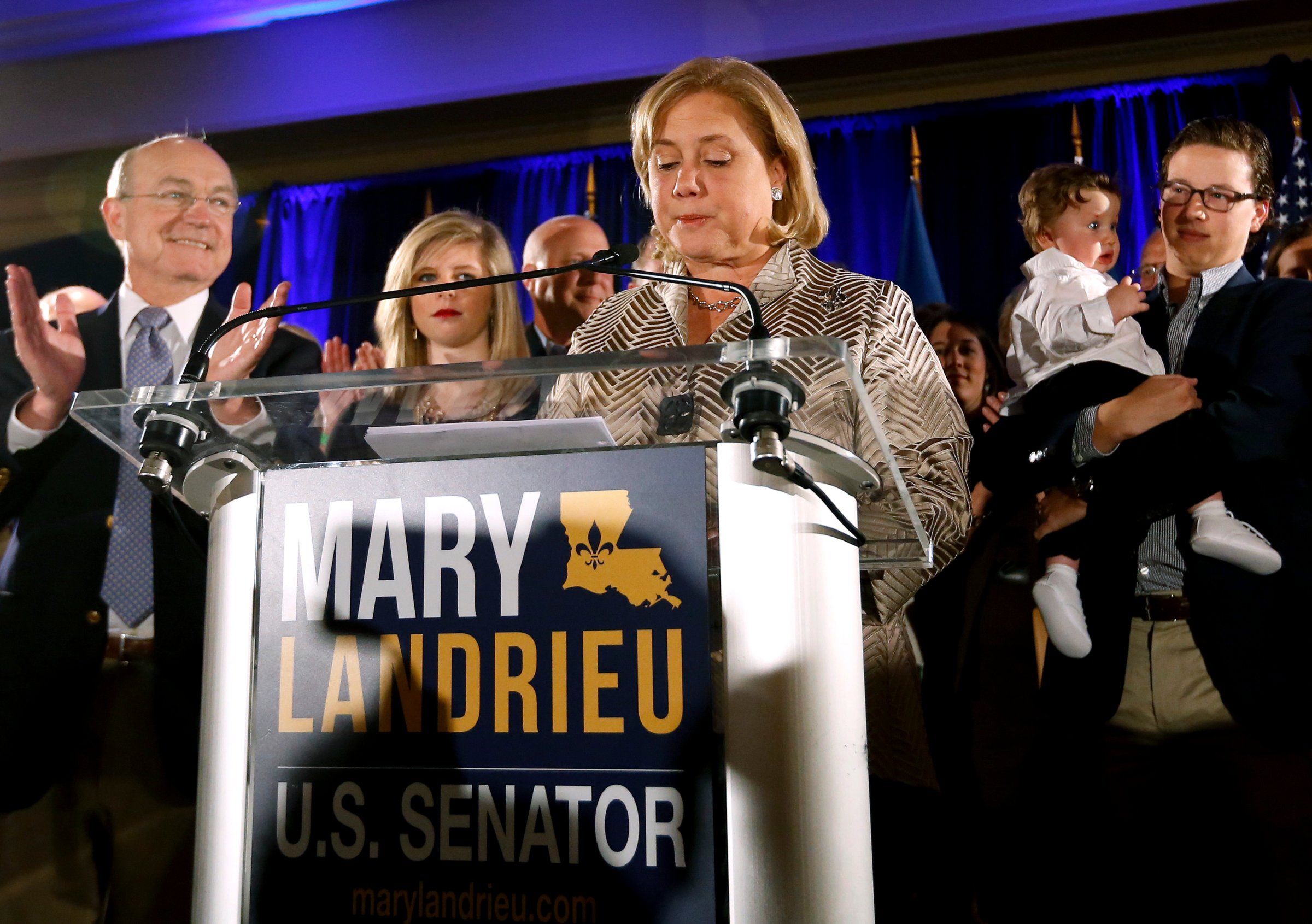

With the fall of three-term Sen. Mary Landrieu Saturday, Louisiana will not have a Democratic statewide elected official for the first time since 1876. And the Republican Party will control, as the Associated Press noted, every Senate seat, governor’s mansion and legislative chamber from the Carolinas to Texas.

Congress’ last white Democrat in the Deep South didn’t lose because of a superior opponent, but because of her association with a deeply unpopular President and a health-care law that destroyed the chances to extend other Democratic dynasties this cycle, including Georgia’s Jason Carter and Michelle Nunn.

Landrieu—the daughter of a former New Orleans mayor and the sister to the current one—lost more so than Republican Rep. Bill Cassidy won. Even Cassidy, who cruised to a win Saturday, acknowledges that to some extent. When asked to define the campaign’s turning point, he pointed to Landrieu’s support of the Affordable Care Act, which passed four years ago.

“I think it’s a referendum on Senator Landrieu’s support for a legacy, which the majority of people in Louisiana disapprove of,” he told TIME of his victory. “Sen. Landrieu has ceased to represent the views of the majority of the people of Louisiana but assumed that the advantages of incumbency would be adequate to ensure her reelection. But the people of Louisiana wanted a senator who represented them not Barack Obama.”

The fact that Landrieu couldn’t beat Cassidy—who Pearson Cross, an associate professor at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, called “not a natural,” “not charismatic,” “off-putting” and “awkward” in a six-minute telephone interview—leads Louisiana election experts to believe that a Democrat won’t win statewide office for years. For Cross, ten to fifteen.

“Early on I said that Cassidy couldn’t win unless he started to run a campaign that was more than people’s negative attitudes about Mary Landrieu,” he says. “But in fact, I was wrong. He has essentially won this campaign without bringing much to the table beyond people’s visceral dislike for Obama and Obamacare.”

In her final days, Landrieu acknowledged her disappointment that the national Democratic organization designated to defend her—the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee—abandoned her after the November 4 election turned to a runoff. Pro-Cassidy outside groups outspent her by a huge amount— a “roughly a 180-to-1 margin” on television, according to a November Associated Press article. Landrieu may be hard pressed not to partly blame the DSCC for her shellacking.

But she also could have run a better campaign. A few weeks ago she tried to display her clout as head of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources by pushing through a bill to approve the Keystone XL pipeline, which failed by one vote. Even if it had gone through it wouldn’t have helped her much, says Joshua Stockley, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Louisiana at Monroe.

“I think that was a bad decision,” he said. “Here in Louisiana the average voter isn’t running around thinking ‘Man, I really wish we had a pipeline right now. Man, I really think oil and gas were cheaper.’ We’re already dealing with the lowest price per bill we’ve seen in decades. … Our day to day conversations aren’t dictated by the Keystone pipeline.”

Stockley says that she could have better emphasized issues like raising the minimum wage, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, Violence Against Women Act and her efforts to keep some major military bases afloat and to reduce college debt. It’s clear, however, that despite Landrieu’s campaigning on these and other issues, one broad statistic—“Mary Landrieu voted with Obama 97% of the time”—was the major theme in the race.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise to Cross—who called Obamacare Cassidy’s “Exhibit A” binding Landrieu to the President—or anyone else for that matter, that Cassidy’s answer to the old question “What is the first bill you’d like to introduce?” focuses on repealing and replacing the health care law. Of course, doing that proves to be an incredible hurdle.

“Will that be the first bill that we’re going to be able to get out?” asked Cassidy. “I don’t know that—probably not. But if you want to talk to the American people … they would love to see that bill, wouldn’t they?”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com